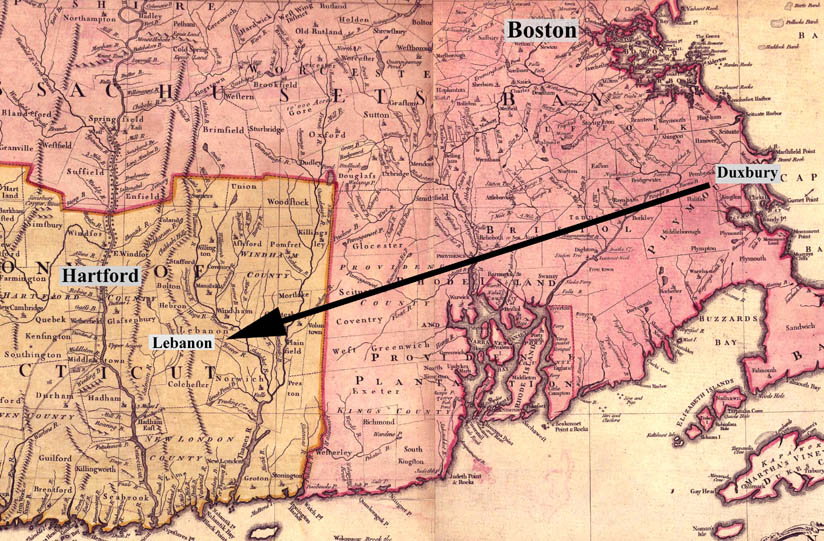

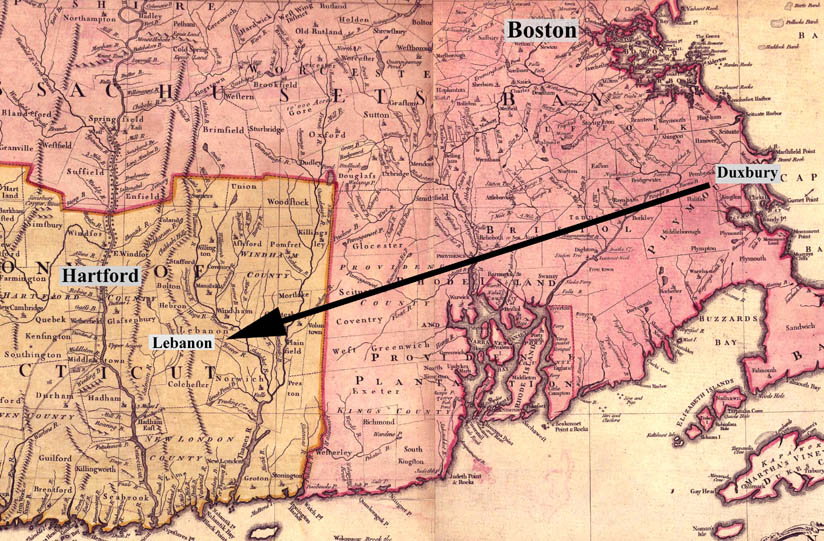

Eighteenth-century map of New England, showing location of Duxbury and Lebanon. Published in London by Thomas Jeffries in 1755. Click image to enlarge.

Eighteenth-century map of New England, showing location of Duxbury and Lebanon. Published in London by Thomas Jeffries in 1755. Click image to enlarge. |

Ephraim Sprague was born on March 15, 1685 in Duxbury, Massachusetts. Duxbury was part of the Plymouth Colony, having become a separate town in 1637. Ephraim Sprague’s great-grandfather, Francis Sprague, had emigrated to Plymouth in 1623 from the west of England, where he had been a tavern-keeper. Francis Sprague’s grandson, John Sprague, was Ephraim Sprague’s father. In 1703, John Sprague sold all his property in Duxbury and relocated his family to Lebanon, Connecticut, where he bought several hundred acres of land; two sons, Ephraim and Benjamin, both young men at the time, came to Lebanon with him.

Soon after the family settled in Lebanon, Ephraim Sprague married Deborah Woodworth;

like the Spragues, the Woodworths had come to Lebanon from southeastern Massachusetts.

Ephraim and Deborah Sprague settled on an extensive tract of land along the Hop River on what was known as

“The Mile and a Quarter.” At the time, the boundaries of the various towns were not entirely delineated,

and there were conflicting claims as to who actually had the right to sell land to settlers like the Spragues;

eventually, the Connecticut legislature had to step in to confirm the titles of Sprague and other nearby landowners.

The portion of his farm on the west side of the Hop River was part of the town of Lebanon, while the portion on the

east side was in Coventry. Between 1705 and 1725, Ephraim and Deborah Sprague had at least eight children:

Perez, Peleg, Ephraim 2nd, Deborah, Betty, Irene, Mary, and Marcy. Deborah Sprague died sometime after 1727.

Other than her first name, Mary, nothing is known about Ephraim Sprague’s second wife.

|

|

A book clasp, such as might be used with a Bible, recovered from the Sprague Site. |

Ephraim Sprague was a leader in the community. In 1722, he and his first wife, Deborah, were founding members of the North Society parish, known as “Lebanon Crank,” that would later form the basis for the town of Columbia. Sprague served the congregation as a deacon, responsible not only for the business dealings of the parish (such as paying the minister) but also for investigating transgressions such as public drunkenness, for which congregants would receive admonishment. In 1743, Sprague was one of several members of the North Society who petitioned the legislature for a separate church society for the families in the north part of Lebanon Crank, the area that would eventually become the town of Andover. That Ephraim Sprague was a man of religious convictions is also apparent from the probate inventory that was compiled after his death in 1754. Of the seven books listed, six were religious in nature: a “great Bible,” a small Bible, "Exposition on ye Rev.", a pamphlet or tract not identified by title, Isaac Watt’s book of psalms, and William Beveridge's "Thoughts on Religion."

Ephraim Sprague’s other volume was an old law book. Like his father before him, he served his community in political office, including two terms as one of Lebanon's selectmen and one as a representative to the colonial legislature.

He also

continued his family's long tradition of military service. His father had been an officer in one of Lebanon's militia units, and his grandfather had

fought (and died) in King Philip's War. Ephraim Sprague was elected captain of the North Parish company of militia in 1724. A militia captain

was responsible for training his men, inspecting their firearms and ammunition, paying them if they were called up for

service, and, of course, commanding them in time of war. Because the men of each company elected their officers, being a captain

meant that Sprague was not only socially prominent but also a person who had the respect of his neighbors. The North Society

company was called to service in 1725 during a conflict with Indians known as Lovewell's War or Greylock's War. Ephraim Sprague

and his men patrolled the Connecticut border with Massachusetts, where an Indian attack was expected at any time.

No attack materialized, but Ephraim Sprague and his men received £83 6s from the Colony of Connecticut for their service.

|

|

Tea pot, creamer, and four tea cups and saucers recovered from the Sprague Site, as cross-mended. |

Because he was a prominent man, we know quite a bit about the public life of Ephraim Sprague from historical documents. To learn more about his private life--what he ate, how he spent his time, what household objects he possessed--we must rely on the archaeology conducted at the site. The picture that emerges is that of a man with some interest in elegant possessions, such as brass cufflinks and an imported tea service, but also a frugal man who mended broken pans, made his own implement handles out of deer antler, and fashioned a woodworking saw out of brass salvaged from an old kettle. At his table, the produce of his farm--corn, potatoes, pork--was supplemented by food he obtained by hunting and fishing. Clothing remains included both homespun cloth and silver thread, again suggestive of an overall modest standard of living with a few luxuries befitting his status as a prosperous farmer and leader of his community.

Ephraim Sprague died shortly after making his last will and testament, which

was dated November 1, 1754. He willed his farm to his 16-year-old grandson, Ephraim Sprague 3rd, the son of Ephraim Sprague 2nd,

who had

died a few years earlier. As was required by law at the time, his "dearly beloved wife" Mary Sprague was given

one third of the farm as her widow's right. Shortly thereafter, Ephraim Sprague 3rd married and moved to Sandisfield,

Massachusetts. It is believed that the widow Mary Sprague remarried in 1762, by which time the Sprague farm had been sold

outside the family to John Gibbs.