The top of the south cellar feature found below the plowed field. In the foreground is the buried bulkhead entrance; the large rectangular-shaped stone is a step. The camera is facing west. Click image to enlarge.

The first architectural evidence of the Sprague House was the discovery of a buried cellar hole

feature

ten to twelve inches beneath the plowed ground surface. The cellar measured 16 x 16 feet; a bulkhead entrance with stone steps extended off the southeast corner. The cellar was filled with field cobbles and boulders, discarded fireplace stones, artifacts from the homestead, and soil. At the bottom of the cellar were remnants of charred boards and large pockets of ash intermixed with burned sherds of ceramics, glass and food remains. The cellar floor was five feet below the ground surface. The cellar walls were straight and firmly lined with dry-laid fieldstone. The bulkhead entrance walls were also lined with fieldstone and its steps were made from large stone slabs. The steps and walls were so well-made that 250 years after their burial, and repeated plowing, the archaeologists could walk down them as though they had just been built.

|

|

Six feet north of the south cellar was a large ash- and stone-filled feature that represents the remains of a large central fireplace. The camera is facing northwest. Click image to enlarge. |

Six feet north of the south cellar, a fireplace feature was discovered, measuring 9 x 7 ½ feet in size. The fireplace’s footing extended 2 feet 8 inches below the ground surface and was filled with ash,

dressed stone

and hearth-related artifacts such as straight pins, European flint strike-a-lights, beads, buttons, tiny bits of burned and

calcined

bone and fish scales. Most of the fireplace’s geometrically-shaped stones, including the large hearthstone, had been removed to be reused elsewhere after the house site was abandoned; such stones were valuable and were often recycled. The fire-degraded stones from the hearth and flue, which could not be reused, were discarded into the cellar hole when it was filled.

|

|

The north cellar of the Sprague house. The camera is facing west. Click image to enlarge. |

About 64 feet north of the south cellar wall a second buried cellar hole was found; it was filled with field

cobbles, pockets of ash, and artifact-rich soil. This northern cellar measured 16 x 14 feet, but unlike the south cellar, it had an uneven floor and its walls were unlined and sloped inward. The east side of the cellar was much deeper than the west side and was 3 feet 7 inches below the ground surface, much shallower than the northern cellar. There was no bulkhead entrance, indicating the cellar was entered through a trapdoor in the house floor. Off the extreme northwest corner of the cellar a square (4 x 4-foot) fireplace feature was discovered filled with stone and thick pockets of charcoal.

Archaeological evidence shows that the Sprague House was built with thousands of hand-wrought nails, and likely covered with wooden clapboards and shingles. The windows were made of small diamond- and triangular-shaped panes held together with grooved pieces of lead called came. There were fragments of large hand-forged strap hinges and latches. Mortar for the stone fireplaces was made from limestone, crushed seashells and local clay. A few red brick fragments found suggest that only the chimney stack above the roofline was bricked, a common technique in the 18th century called “topping out,” which gave the house the appearance of having a brick chimney, which was more expensive than a stone chimney.

Concentrations of carbonized food remains, charred boards, burned ceramics and melted bottle and window glass found in the cellars indicate that the Sprague House burned down in a catastrophic fire in the 1750s (no artifacts made after this date were found). Soon thereafter, the fireplaces were dismantled, the cellars were filled and buried, and the home lot was converted into an agricultural field; it remained a field until the archaeological investigations began. Although the fire was a great loss to the Spragues, it was a boon for archaeologists because it promoted preservation of artifacts and food remains that would normally be consumed by Connecticut’s acidic soils.

|

|

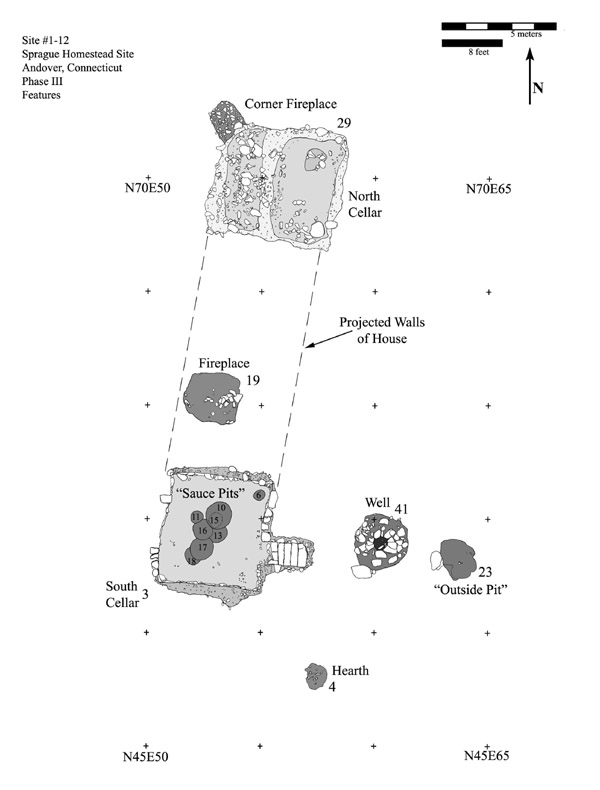

Plan drawing of the features found at the Ephraim Sprague House Site. Click image to enlarge. |

The house’s long and narrow (72 x 16 feet) dimensions, as well as the distributions of artifacts and features, suggest the Sprague House was a type of cross-passage house that was common in Britain in the 1600s when New England’s colonization began. Cross-passage houses are related to earlier “longhouses,” which had a byre or shippen at one end for keeping dairy cows. Cross-passage and longhouse houses were built with a wide hallway or passage that perpendicularly bisected the house. As far as we know, there are no cross-passage houses still standing in North America. Most were built in the early 1600s or on the early 18th-century frontier, like the Sprague House; we only know they existed because of the discoveries of archaeologists in the field and research by historians in archives.

The Sprague House was originally interpreted as having a cross-passage near the parlor with a double-sided fireplace in the middle of the house. After discussing the site with Cary Carson, retired vice president of research at Colonial Williamsburg, and an expert on early English architecture, the house plan was revised to reflect more of a typical West Country cross-passage house. This included moving the cross-passage to between the pantry and hall and expanding the size of the parlor to enclose the corner fireplace.

No subsurface foundation stones or footings were found during the excavations because the house had been built using a

foundation-on-ground

technique, whereby the house sills sat directly on a fieldstone foundation that rested on top of the ground

surface. When the above-ground burned house remains were removed in the 1750s and the home lot converted into an

agricultural field, the foundation stones were apparently picked up and either discarded or reused elsewhere

because they would impede plowing over the site; thus there is no physical trace of where they had been.

However, the stone walls of the two cellars line up perfectly, and the large central hearth is between the

cellars, so we can project the house footprint and the wall lines connecting the two house ends.

|

|

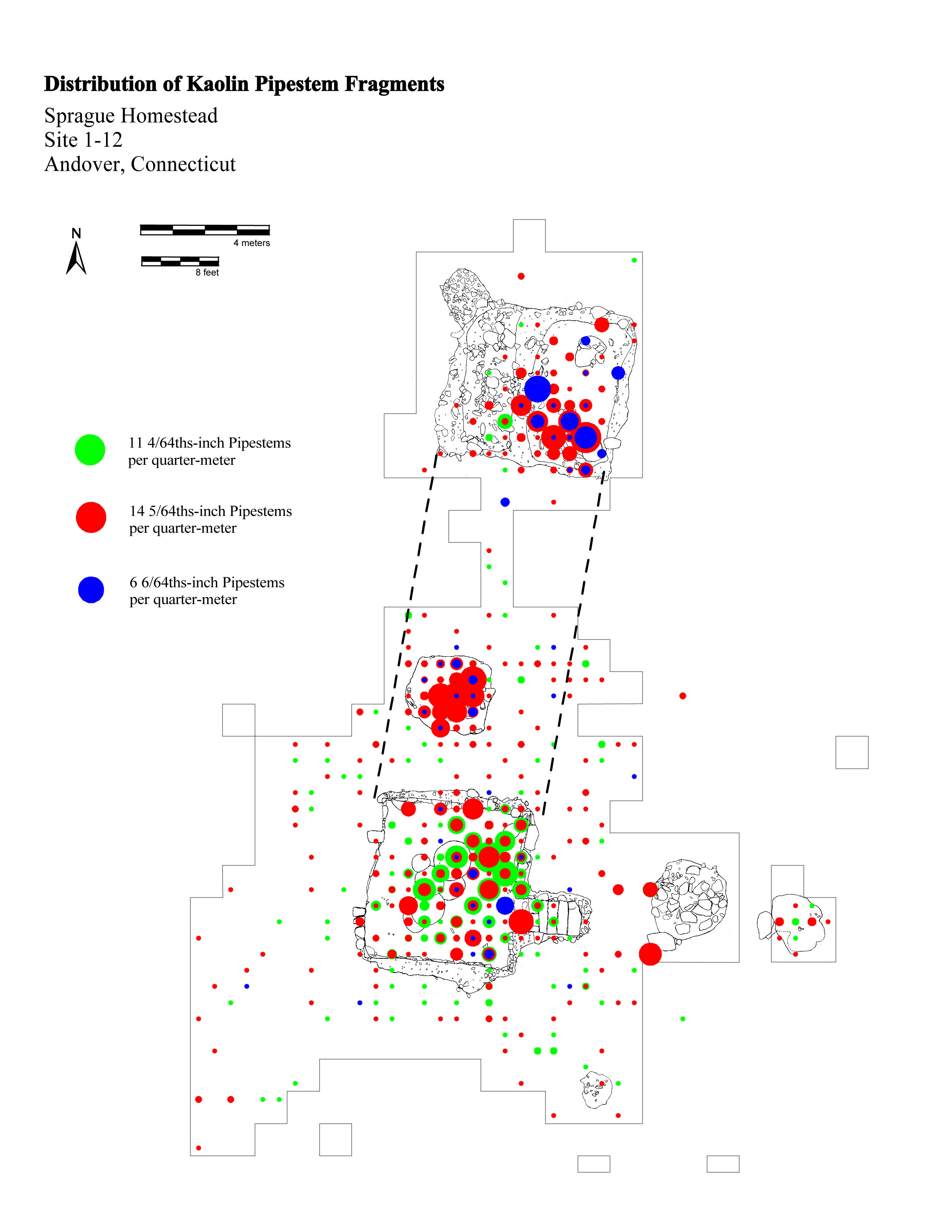

Distribution of tobacco pipe stems. Click image to enlarge. |

|

|

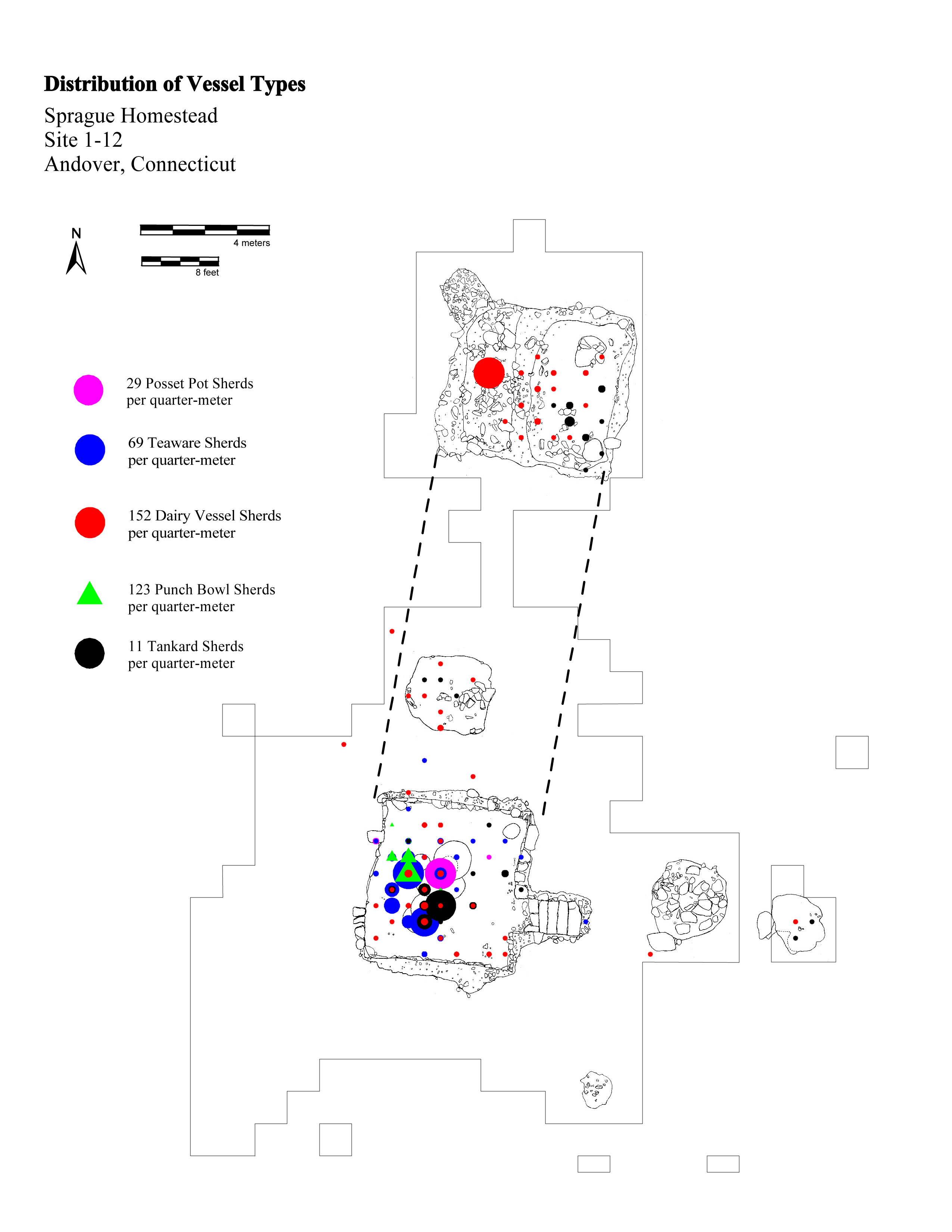

Distribution of ceramic vessels after cross-mending. Click image to enlarge. |

Based on the distributions of datable artifacts such as tobacco pipes, a spoon and other items,

the north cellar may have been the original "starter house" built by Ephraim Sprague and his wife Deborah

Woodworth around 1705, perhaps measuring just 20 x 20 feet. After a few years the Spragues appear to have

expanded the structure to the south, creating their long and narrow cross-passage house. The starter house area also

contained a greater diversity of wild game, not unexpected at an early frontier house.

Adjacent to the kitchen, which was south of the central fireplace, the pantry over the south cellar was used to store food, dishes and utensils. Meals were prepared in the kitchen and most of the family ate and spent time in the hall, visiting and working. The heated parlor in the northwest corner, in the original portion of the house, was likely reserved for Ephraim Sprague, the head of the house, to conduct business and meet with church elders, militia officers and government officials. The Spragues had, in effect, created their own sort of manor house on the Connecticut frontier.

Other features discovered at the site include a stone-lined well off the kitchen, an outside hearth, and an

exterior feature that may have been a food-storage pit but was later used as a trash pit. The area east of the

house was likely the yard, where outside work such as laundry, soap-making and yarn-dyeing was done.

Fifty feet southeast of the house was a large midden or household refuse-dumping area.